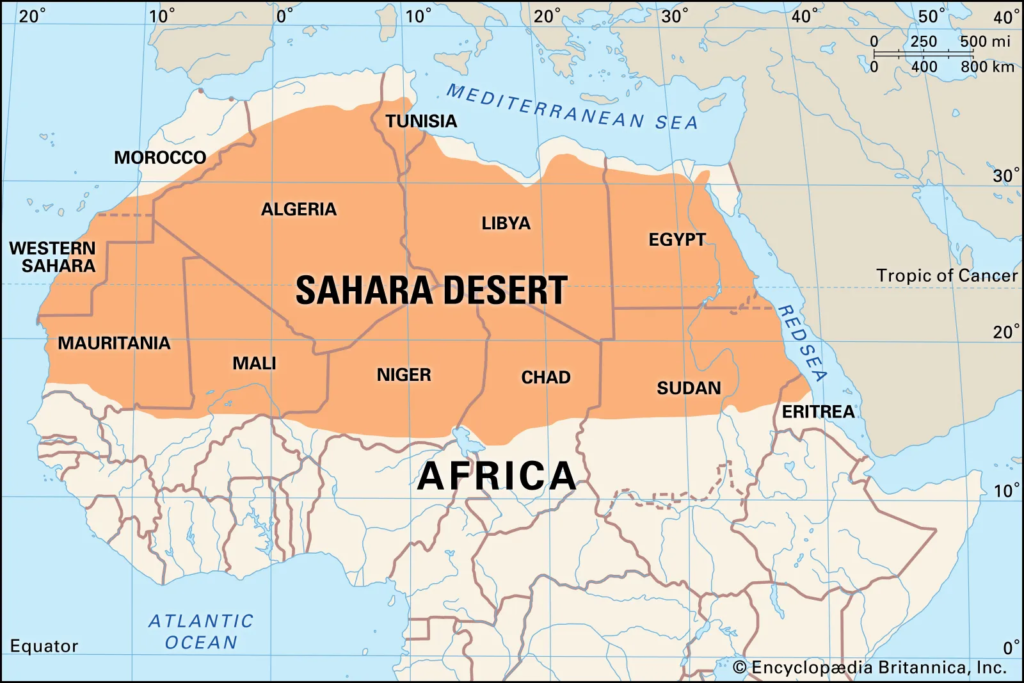

The Sahara Desert and North Africa, in general, represent one of the world’s greatest untapped energy resources. The solar energy that strikes the surface of this desert has the potential to power the entire world. A single solar panel placed in Algeria can generate three times more electricity than the same panel placed in Germany. What was once a geographic disadvantage—the scorching sun of these desolate lands—could now provide an economic boom for these historically impoverished nations.

A solar panel in a farm located here, one square metre in size, would, on average, generate five to seven kilowatt-hours of energy each day. Increase that to one square kilometre, and we are generating five to seven gigawatt-hours of energy daily. Scale it up to one thousand square kilometres, and we are generating five to seven terawatt-hours of energy each day, enough to satisfy nearly 100% of Europe’s energy needs. Multiply that by ten, and we are generating 50 to 70 terawatt-hours a day, enough to power the entire world. This is an impressive and often repeated statistic, a napkin calculation that paints a drastic new vision of a solar-powered utopia.

Plans have even been drawn up to transform these simple mathematics into reality. However, reality has a way of interfering with such futuristic, pie-in-the-sky calculations. Every plan to turn this dream into reality has faced significant challenges. In this episode, we will explore why.

The Challenge of Transporting Electricity

Transporting electricity out of these remote regions is the first challenge. Currently, there are only two interconnections connecting North Africa to Europe, both located between Morocco and Spain. These are two 700-megawatt interconnections, one completed in 1998 and the second in 2006, with a third connection expected to be completed before 2030, bringing the total to 2,100 megawatts. To transport enough electricity to power Europe, ignoring transport losses and storage issues, we would need 592 to 831 more of these 700-megawatt interconnections.

These aren’t just simple cables laid between countries; they are incredibly complicated and expensive pieces of infrastructure. The third interconnection joining Morocco and Spain’s grids is estimated to cost $150 million, an enormous investment split between both countries. Building 592 more of these connections would cost at least $8.9 billion, calculated by simply multiplying $150 million by 592. These connections are the shortest route to Europe from North Africa, making them the cheapest to build. To create a truly interconnected grid, we would need even longer interconnections connecting Tunisia to Sicily, Algeria to Sardinia, Libya to Crete, and onwards to Greece and Turkey, while also building enough internal interconnections in Europe to facilitate the passing of solar power northwards while the wind is traded south.

This plan will take billions to complete. Yet, even with these issues, European leaders have drawn up plans to connect North Africa and the Middle East to Europe, believing the cost can be recovered.

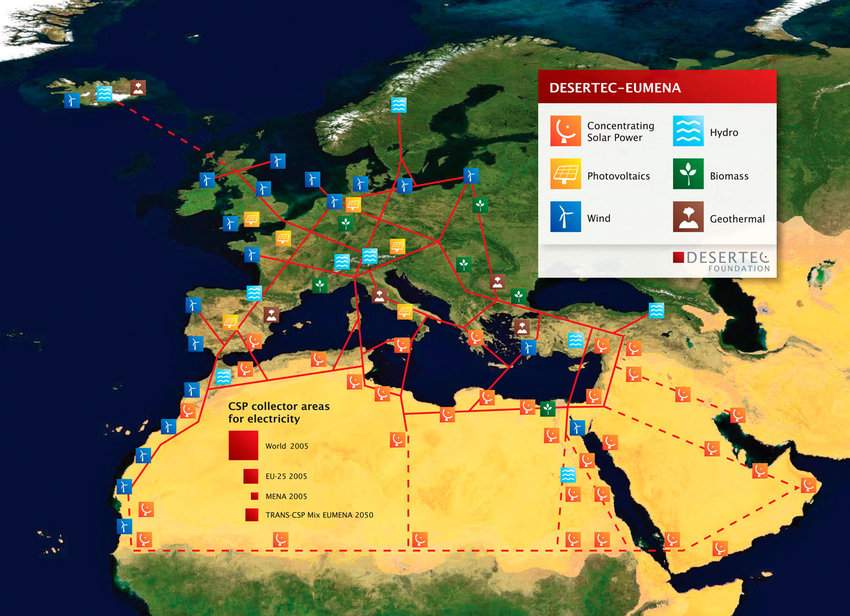

The Desertec Initiative

Desertec was, or perhaps more appropriately, a German-led initiative centred around a half-trillion-dollar investment fund aimed at investing in generation and transmission infrastructure across North Africa and the Middle East. $55 billion was allocated to increasing transmission capabilities across the Mediterranean. This investment would go into both high voltage alternating current (HVAC) transmission over shorter gaps, like those from Morocco to Spain, and high voltage direct current (HVDC) over longer distances.

There is a critical distance where HVAC transmission does not make sense. If we plot transmission losses per kilometre for AC and DC transmission, it would show that DC loses less power per kilometre. However, to convert regional AC grid power to DC for these long-distance transmission cables, expensive transformers and converters are needed. If we plot cost versus distance, including this infrastructure, we see that DC and AC lines cross each other around the 500 to 800-kilometre mark. This is the break-even point where DC becomes more cost-effective. Therefore, lines connecting Morocco directly to Spain, which span only 28 kilometres, don’t make sense for HVDC, while longer lines connecting Tunisia to Italy will likely be HVDC.

Transmission losses for HVDC are about 3% per 1,000 kilometres, and Germany’s capital is only 1,800 kilometres from Tunisia. Transmitting power with this much investment money is perfectly feasible, and the technologies exist.

Concentrated Solar Power: A Viable Solution?

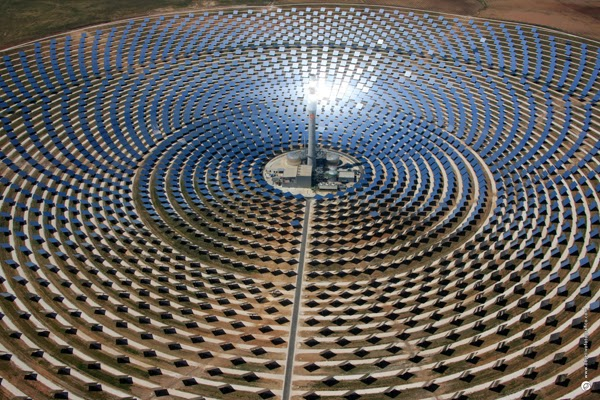

Let’s move into the generation part of the Desertec plan. Desertec was formulated with concentrated solar power (CSP) in mind, which works very differently from photovoltaic (PV) solar panels. CSP facilities would be spread out along the borders of the Saharan and Arabian deserts. One such facility already exists in Morocco, and it’s the largest CSP plant in the world. It is massive, with three separate sections: Noor I, II, and III, each using slightly different variations of CSP, combining to provide 510 megawatts.

Noor I and II are both trough-based systems that use parabolic mirrors with a tube located in the mirror’s focal point. The tube contains synthetic oil, which collects heat from the 500,000 parabolic mirrors spread out over 308,000 square metres. This oil becomes extremely hot, reaching as high as 400 degrees Celsius, allowing it to boil water in a heat exchanger to drive a steam turbine, which provides electricity for the grid. The 400-degree oil is also hot enough to melt salt in a molten salt heat storage system. The molten salt heat storage system of Noor I can store enough heat to keep the plant operational for three hours, while Noor II has enough energy for seven hours. However, this salt solidifies at 110 degrees, and if that happens, the plant won’t work in the morning. Therefore, Noor I and II need a fossil fuel burning system to keep all the working fluids of the system at minimum operating temperatures overnight and to keep the oil system pumping. This fossil fuel burning system can also keep the plant operational as a reliable baseline energy source, removing the need for separate natural gas peaker plants.

Noor III does not use these parabolic mirrors and instead uses a tower system. It’s this striking circular facility to the north that looks less like an industrial facility and more like a new-age Burning Man art installation. This design allows Noor III to rid itself of the oil plumbing and pumps of Noor I and II. Instead, it uses mirrors arranged in concentric circles around a central tower. The mirrors are then controlled to focus light on a single point on the tower, which directly heats the molten salt, which is the working fluid instead of the oil-based system. The solar concentration here is much higher, and in turn, the temperatures attained are much higher, with the water being heated to 550 degrees. This allows the tower-based system to use more efficient steam turbines, and using molten salt as the working fluid removes the need for an oil-to-molten-salt heat exchanger in the heat storage system.

Noor III is the world’s only operating tower-based CSP system with molten salt storage after the 2019 shutdown of Nevada’s Crescent Dunes plant. The Crescent Dunes plant ceased operation in 2019 after only four years of operation. NV Energy broke its purchasing contract with the plant after it failed to meet performance requirements, being marred by maintenance issues, including an eight-month shutdown due to a leak in the molten salt tank. Even when fully operational, the plant’s electricity cost $135 per megawatt hour, while a nearby PV plant was managing $30 per megawatt hour.

The Rise of Photovoltaics

Here lies the crux of the issue: CSP costs per megawatt were extremely competitive with photovoltaics in 2009, but in the last decade, photovoltaics have become obscenely cheap. CSP simply cannot compete in a market like this, and the same can be seen for Noor I, II, and III. However, they are currently being measured on a metric called the levelized cost of electricity, which is an average of the cost to generate electricity over the entire life of the plant. However, this does not factor in the cost of storage for photovoltaics, which is often just an inherent benefit of CSP. Going forward, the industry should use a combined cost of storage and cost of electricity metric.

Yet, the most recent addition to this solar farm is Noor IV, a solar panel farm contributing 73 megawatts. With the rise of cheap solar panels, Desertec, contrary to what you might expect, was doomed for failure. CSP, by nature, needs a lot of land. The plant has a minimum viable operating temperature, and to achieve that, we need enough mirrors to reflect light. Solar panels do not have this problem. They can be fitted on top of homes, over car parks, or even in farmers’ fields to help shade plants that need shade. We don’t need massive plots of land to make them work, and because they are so cheap, it’s perfectly feasible to build smaller solar farms in Germany and avoid those transmission losses, not incurring the massive financial risk of investing billions into a country that is not your own.

That’s particularly important because a lot of investors are very hesitant to put money into these often volatile countries. We need to look no further than the 2013 attack on a BP natural gas plant in Algeria to see why this would be considered a risky investment. It’s a vital economic resource for Algeria, yet it sits isolated amid a vast desert that’s a transit route for Al-Qaeda in North Africa. No wonder it was so difficult to defend and such a tempting target for militants.

A New Vision for Africa’s Solar Future

This is all exactly why Germany is instead investing in its domestic photovoltaic generation. In 2020, solar power accounted for 10% of Germany’s power generation. This idea of European countries drawing natural resources from Africa to benefit their own economy has some undeniable problematic historical parallels. Any foreign investment like this is going to come with some guarantees of supply for Europe, beyond the difficulties of organising cross-border cooperation like this. That’s not going to go down well when the country hosting these plants needs the power for their grid to power their economy or simply stabilise their grid for current needs.

It becomes even more problematic when you consider the amount of water these facilities need for cooling the steam turbine and keeping the mirrors clean. This facility in Morocco uses 2.5 to 3 billion litres of water every year, taking water from a dam 12 kilometres away. Morocco is already susceptible to droughts, so scaling these water demands up just to feed Europe’s power needs while taking water away from the farms that feed Moroccan citizens is even more problematic.

To truly scale this power generation, some technological improvement that reduces the consumption of water would be needed, or just pair the facilities with desalination plants and use the extra water, if any, to irrigate local farms to boost local economies even more. For this dream of turning the earth’s barren deserts into energy generation centres to come true, it has to be a grassroots movement, not some new-age imperialism mega-project that comes with a whole host of guarantees in exchange for the nearly half trillion-dollar investment.

North Africa is one of the hardest-hit regions in the world by climate change, with desertification and water scarcity becoming serious issues. This plan, despite its surface-level good intentions, sought to exploit these countries that have suffered the most as a result of Western industrialisation. We don’t need to look for proof that this was their intention. The moment the technology developed to allow European countries to provide their renewable power needs within their own borders, the plan disintegrated. The plan was never about helping African nations.

But the idea isn’t dead in the water. These countries do have the natural resources to benefit from solar energy. Morocco is in the best position to lead by example. Its proximity to Spain allows relatively short interconnections to the European grid. Its government is relatively stable compared to its North African neighbours, with a political stability index of -0.33. Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt are all much lower. While Morocco has abundant solar resources, it also benefits from consistent desert winds along its coast. Morocco has the potential to invest in its own energy needs while exporting excess to Europe, leading by example, slowly shifting away from being a net energy importer of fossil fuels and becoming an energy exporter.

Local infrastructure to benefit local people first—an African nation using its resources to benefit itself first and foremost. The potential for Africa’s solar energy future is undeniable. The technologies to facilitate cross-border energy trading exist, and investments are happening to increase trade capacity, with this third interconnector between Morocco and Spain funded equally by both sides, ensuring a level playing field.

Figuring out the best practice for growing and improving our electric grids is incredibly complicated. Electricity grids are effectively the largest machines on the planet, with hundreds of generators scattered across countries, connected together by wires, relays, and switches. The task of managing that by hand and making sensible decisions for a single human is impossible. More and more of the grid infrastructure is turning towards a smart grid controlled by algorithms. Battery firms employ coding and math experts to develop algorithms to allow them to buy and sell the electricity they store to maximise profit. Coding jobs like that are some of the best-paid and highest demand in the world today.